Pat Ferguson

Ben Reynolds

Two simple words can best describe the events of the revolution, in terms of warfare, terror and resistance. A few factors, common to society, provoked the famous period known as the revolution, “its ongoing foreign and civil war, multilayered internal political strife, constitutional paralysis, economic hardships, religious conflict, and the innovative nature of revolutionary language.”[1] Though these are all common themes that occurred throughout history, the culmination of all of them seemed to stress the French peasants more so than any other group in history. The events that followed these issues though, were quite unique and still remain unique to that single period of time in French history.

The chaos and disorder brought about by the revolution presented a difficult task for the revolutionary leaders with respects towards maintaining organization in the country. The twelve-member committee placed in charge of maintaining order within the country was the Committee of Public Safety or the CPS. The revolutionaries presented a new Constitution whose aim was to produce a new democracy and economic equality, however, the CPS argued that they couldn’t obtain control over the control whilst they were confined by the laws of a constitution. Instead of a democracy, the CPS opted to control with a form of government known as “the terror”. The terror allowed the CPS to use power to maintain control. Those who opposed the actions of the CPS were charged with treason as counterrevolutionaries and sentenced to death in the guillotine. The counterrevolutionaries were the main focus of the Terror government. There were many confrontations during this time, such as between the Republican forces and the peasants in Vendee.

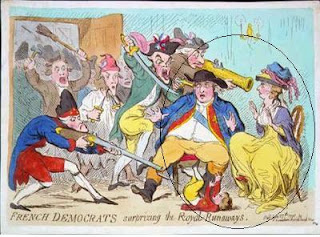

The terror proved to be a very effective form of government to maintain control after the revolution; however, people like Georges Danton began to speak out, saying the violence had been over enforced. The CPS eventually began to lose control with their Terror government as the people of the revolution began to realize that the idea of revolution that they had fought for wasn’t properly manifesting itself in the Terror government. This picture entitled “French Democrats surprising the Royal Runaways” depicts an assault by the Revolutionaries on a family of the prior nobility. During the “Reign of Terror” the revolutionaries fought to get rid of all possible revolutionaries, even if they were only loosely connected to the previous nobility.

The terror proved to be a very effective form of government to maintain control after the revolution; however, people like Georges Danton began to speak out, saying the violence had been over enforced. The CPS eventually began to lose control with their Terror government as the people of the revolution began to realize that the idea of revolution that they had fought for wasn’t properly manifesting itself in the Terror government. This picture entitled “French Democrats surprising the Royal Runaways” depicts an assault by the Revolutionaries on a family of the prior nobility. During the “Reign of Terror” the revolutionaries fought to get rid of all possible revolutionaries, even if they were only loosely connected to the previous nobility.Second, the emergence of revolution focused the lens of terror upon those of the counterrevolution. Main counter revolutionists such as the Queen of France, Marie-Antoinette, saw the constricting terrors. The CPS viewed the queen as a popular monarchial figure who other foreign powers could assemble behind. Because of her supreme power revolutionists tried and executed Antoinette in order to enforce terror upon higher society. Also, this can be seen in the depiction of noble executions. Journee du Janvier’s The Execution of Louis XVI

(displayed right), shows the epitome of terror used by revolution artists. The Specific purpose of this art was designed to terrorize the noble elite. If such terrible things could be done to a ruling king, nothing prevented the same troubles from befalling onto counter revolutionist nobles. These actions terrorized the other members of the ruling elite thus solidifying revolutionary views within the elite of society. These moves by the CPS instigated an emergence of extremist radicals that attacked on the political front. There were vicious verbal attacks made upon the peasants who were attempting to secularize society. Also, France saw the rising importance of education and a decrease in Christianity. The foundations of which were rooted in the Enlightenment. Since the revolution was on the tail ends of the Enlightenment, many of its themes and trends extended into the late eighteen hundreds. These trends included the rising importance of education among people in order to promote the glory of French society. On the other hand, because of the Enlightenments trend of reason, the people of France made specific moves to de-Christianize society and politics.

(displayed right), shows the epitome of terror used by revolution artists. The Specific purpose of this art was designed to terrorize the noble elite. If such terrible things could be done to a ruling king, nothing prevented the same troubles from befalling onto counter revolutionist nobles. These actions terrorized the other members of the ruling elite thus solidifying revolutionary views within the elite of society. These moves by the CPS instigated an emergence of extremist radicals that attacked on the political front. There were vicious verbal attacks made upon the peasants who were attempting to secularize society. Also, France saw the rising importance of education and a decrease in Christianity. The foundations of which were rooted in the Enlightenment. Since the revolution was on the tail ends of the Enlightenment, many of its themes and trends extended into the late eighteen hundreds. These trends included the rising importance of education among people in order to promote the glory of French society. On the other hand, because of the Enlightenments trend of reason, the people of France made specific moves to de-Christianize society and politics.France was barely a nation at the end of the conflicts known as the revolution. The bloodshed finally led to the insertion of a basic authority, which ultimately resulted in the new constitution in the year 1795. The horrible actions of the French peasants seemed fruitless though, as the constitution focused on protecting the rights of nobles rather than the rights of the majority of the population. The extreme actions of the peasants brought more shame than good, as is said, “The experience of the Terror had altered definitively outsiders' views of France, driving it from sympathy in 1789 to hostility and derision by 1795.”[2] Though a new constitution was in place, power still fluctuated and led to further unrest. At the close of the revolution, the Directory, which was made up of five rotating directors, came to power with the help of Napoleon’s military. This form of government was short lived though because a delegate, Sieyes, saw the nation moving towards anarchy and suggested a reorganization of the government. The power of government shifted to a three man consulate consisting of Seiyes, Bonaparte, and Ducos and the nation was in a state of an undetermined governmental authority; it was not a democracy, yet not a liberal government. Napolean Bonaparte, after accepting his position in the consulate just a few months earlier, took over France and crowned himself the emperor. The Revolution was now over and France was basically back to state which the Revolution began in; a monarchial nation favoring the nobility.

The Revolution started off with revolt from the peasants because of oppression and monarchial power, and it ended with the installment of a new monarchial power and oppression once again. As power fluctuated and peasant revolts continued, France remained in a state of governmental disarray and confusion. Four different forms of government were installed and fell within the short span of the Revolution and the peasants found themselves back at square one, with a monarch once again.

[1] War, Terror, and Resistance (pg 1)

[2] War, Terror, and Resistance (pg 5)

France was a country that depended heavily on the well-being of its colonies. The country’s success was due in part to the amount of slave laborers that worked their fields/.However, the course of the revolution brought about repercussions in France’s Caribbean colonies, which had a direct correlation to France’s economy. Some French citizens attempted to abolish such use of slaves with the organization of a club known as the Friends of Blacks. Unfortunately, the majority of French Revolutionaries did not view the issue as a problem. To their surprise, slaves in St. Dominique led an uprising which caused the Legislative assembly in Paris to resort to unpr

France was a country that depended heavily on the well-being of its colonies. The country’s success was due in part to the amount of slave laborers that worked their fields/.However, the course of the revolution brought about repercussions in France’s Caribbean colonies, which had a direct correlation to France’s economy. Some French citizens attempted to abolish such use of slaves with the organization of a club known as the Friends of Blacks. Unfortunately, the majority of French Revolutionaries did not view the issue as a problem. To their surprise, slaves in St. Dominique led an uprising which caused the Legislative assembly in Paris to resort to unpr

(Pilage de la maison de St. Lazare, from

(Pilage de la maison de St. Lazare, from

n the picture the king, a noble, and even a member of the clergy, representing the first and second estates are on top of a suffering peasant, which represents the third estate. The Third estate was suffering before the French Revolution started, primarily because of their huge population. France had 20 million people living within

n the picture the king, a noble, and even a member of the clergy, representing the first and second estates are on top of a suffering peasant, which represents the third estate. The Third estate was suffering before the French Revolution started, primarily because of their huge population. France had 20 million people living within