Patrick Ferguson

Ryan Poehner

In the times prior to World War 1, men held a majority of the roles important to life, while women were seen as caretakers of the home and children. However, during the Great War many of the roles separated by gender were twisted with the absence of men in the country. In World War 1 the roles for men and women were changed. Women’s roles were extended into various industries supporing the war in the home front as well as continuing to run their homes effciently. Women’s roles also streched into the army, where they served as soldiers proper. Simultaneously, men were being recruited more and more to serve their countries with courage and honor by joining the army.

In World War 1, also referred to as the Great War, each gender played large rolls in the war efforts. The women on the Home Front, while the men acted on the Front Lines. The men were attracted to the positions in the army because of their masculine appeal. In many of the posters that the government used to advertise positions in the army openly displayed the masculinity of the soldiers as to make war, and heroism, appeal romantically to the men. One of the posters[1] displays a tank majestically jumping over trenches in front of an orange sunset, similar to a whale breaching and jumping in the ocean during a sunset. This poster is specifically meant to arouse men and their masculinity, rather than being seen as frail, weak, or even cowardly. Shakespeare says it best in Henry V “[they] hold their manhoods cheap whiles any speaks/ That fought with us upon Saint Crispin’s day.”[2] In this part of the play Henry rallies his troops to fight for him boldly and

the war efforts. The women on the Home Front, while the men acted on the Front Lines. The men were attracted to the positions in the army because of their masculine appeal. In many of the posters that the government used to advertise positions in the army openly displayed the masculinity of the soldiers as to make war, and heroism, appeal romantically to the men. One of the posters[1] displays a tank majestically jumping over trenches in front of an orange sunset, similar to a whale breaching and jumping in the ocean during a sunset. This poster is specifically meant to arouse men and their masculinity, rather than being seen as frail, weak, or even cowardly. Shakespeare says it best in Henry V “[they] hold their manhoods cheap whiles any speaks/ That fought with us upon Saint Crispin’s day.”[2] In this part of the play Henry rallies his troops to fight for him boldly and  honorably, exactly the same as the task that Britain is faced with in WWI. This idea of cowardice and bravery is reflected in Erich Maria Remarque’s first-hand-account of the War to End All Wars, All Quiet on the Western Front. In this novel Kantorek, a high school teacher, inspires a group of young men to enlist in the German army to defend their country

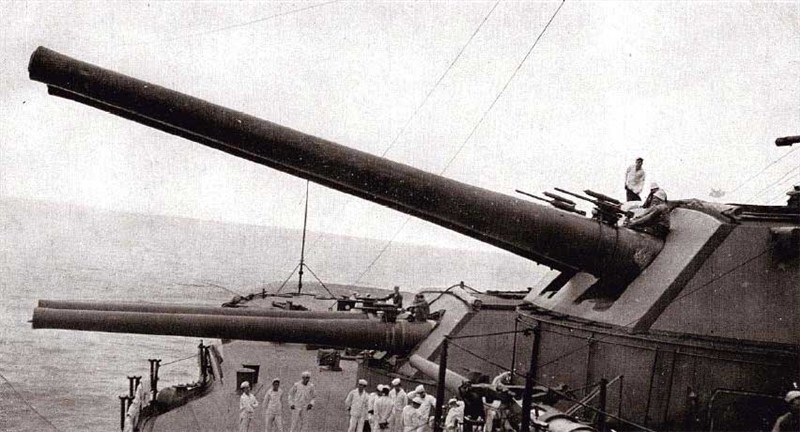

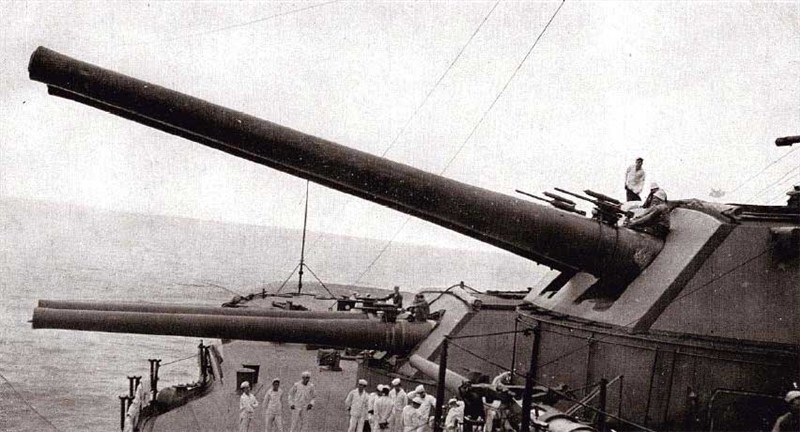

honorably, exactly the same as the task that Britain is faced with in WWI. This idea of cowardice and bravery is reflected in Erich Maria Remarque’s first-hand-account of the War to End All Wars, All Quiet on the Western Front. In this novel Kantorek, a high school teacher, inspires a group of young men to enlist in the German army to defend their country . Kantorek is constantly romanticizing about the war and the positives of serving for their country. As a result of his teachings, many of the boys enlist in the army to honorably serve their country. With Social Darwinism becoming popular in the beginning of the war, each country is trying to promote its fitness and countries can prove their fitness through war and winning battles. One of the most important aspects to the fitness of one’s country was the weaponry that was being used.[3] In most cases the large cannons were seen as direct images of masculinity because of the amount of power that they contained, and the soldiers’ ability to tame that power. The Romantic view of war and heroism made it important for men to display their masculinity through war, as a soldier.[4]

. Kantorek is constantly romanticizing about the war and the positives of serving for their country. As a result of his teachings, many of the boys enlist in the army to honorably serve their country. With Social Darwinism becoming popular in the beginning of the war, each country is trying to promote its fitness and countries can prove their fitness through war and winning battles. One of the most important aspects to the fitness of one’s country was the weaponry that was being used.[3] In most cases the large cannons were seen as direct images of masculinity because of the amount of power that they contained, and the soldiers’ ability to tame that power. The Romantic view of war and heroism made it important for men to display their masculinity through war, as a soldier.[4]

In World War 1, also referred to as the Great War, each gender played large rolls in

the war efforts. The women on the Home Front, while the men acted on the Front Lines. The men were attracted to the positions in the army because of their masculine appeal. In many of the posters that the government used to advertise positions in the army openly displayed the masculinity of the soldiers as to make war, and heroism, appeal romantically to the men. One of the posters[1] displays a tank majestically jumping over trenches in front of an orange sunset, similar to a whale breaching and jumping in the ocean during a sunset. This poster is specifically meant to arouse men and their masculinity, rather than being seen as frail, weak, or even cowardly. Shakespeare says it best in Henry V “[they] hold their manhoods cheap whiles any speaks/ That fought with us upon Saint Crispin’s day.”[2] In this part of the play Henry rallies his troops to fight for him boldly and

the war efforts. The women on the Home Front, while the men acted on the Front Lines. The men were attracted to the positions in the army because of their masculine appeal. In many of the posters that the government used to advertise positions in the army openly displayed the masculinity of the soldiers as to make war, and heroism, appeal romantically to the men. One of the posters[1] displays a tank majestically jumping over trenches in front of an orange sunset, similar to a whale breaching and jumping in the ocean during a sunset. This poster is specifically meant to arouse men and their masculinity, rather than being seen as frail, weak, or even cowardly. Shakespeare says it best in Henry V “[they] hold their manhoods cheap whiles any speaks/ That fought with us upon Saint Crispin’s day.”[2] In this part of the play Henry rallies his troops to fight for him boldly and  honorably, exactly the same as the task that Britain is faced with in WWI. This idea of cowardice and bravery is reflected in Erich Maria Remarque’s first-hand-account of the War to End All Wars, All Quiet on the Western Front. In this novel Kantorek, a high school teacher, inspires a group of young men to enlist in the German army to defend their country

honorably, exactly the same as the task that Britain is faced with in WWI. This idea of cowardice and bravery is reflected in Erich Maria Remarque’s first-hand-account of the War to End All Wars, All Quiet on the Western Front. In this novel Kantorek, a high school teacher, inspires a group of young men to enlist in the German army to defend their country . Kantorek is constantly romanticizing about the war and the positives of serving for their country. As a result of his teachings, many of the boys enlist in the army to honorably serve their country. With Social Darwinism becoming popular in the beginning of the war, each country is trying to promote its fitness and countries can prove their fitness through war and winning battles. One of the most important aspects to the fitness of one’s country was the weaponry that was being used.[3] In most cases the large cannons were seen as direct images of masculinity because of the amount of power that they contained, and the soldiers’ ability to tame that power. The Romantic view of war and heroism made it important for men to display their masculinity through war, as a soldier.[4]

. Kantorek is constantly romanticizing about the war and the positives of serving for their country. As a result of his teachings, many of the boys enlist in the army to honorably serve their country. With Social Darwinism becoming popular in the beginning of the war, each country is trying to promote its fitness and countries can prove their fitness through war and winning battles. One of the most important aspects to the fitness of one’s country was the weaponry that was being used.[3] In most cases the large cannons were seen as direct images of masculinity because of the amount of power that they contained, and the soldiers’ ability to tame that power. The Romantic view of war and heroism made it important for men to display their masculinity through war, as a soldier.[4]

During the beginning stages of the First World War, many women jumped on the nationalistic band wagon. While it was highly uncommon for women to support their country by fighting on the front lines, there was an overwhelming opportunity for them to help back on the home fron t. Organizations such was the Queen Mary’s Army Auxiliary Corps (QMWAA), served as an outlet for these ambitious women. Also the new dependencies on industrial production allowed for women to find work in places such as munitions factories. For example, in the beginning of WWI in Britain, close to one million lower class women soon found themselves working the munitions plants of Britain. These women soon became known as “munitionettes”. One downside to becoming a woman activist is that munitions experts and employees’ work contributes to the fighting, they are not able to profess their pacifism. The soon increasing

t. Organizations such was the Queen Mary’s Army Auxiliary Corps (QMWAA), served as an outlet for these ambitious women. Also the new dependencies on industrial production allowed for women to find work in places such as munitions factories. For example, in the beginning of WWI in Britain, close to one million lower class women soon found themselves working the munitions plants of Britain. These women soon became known as “munitionettes”. One downside to becoming a woman activist is that munitions experts and employees’ work contributes to the fighting, they are not able to profess their pacifism. The soon increasing  nationalism created by these women in factories soon spread to other sections of Europe. In Scotland in 1918 some shell working Scottish women raised and funded the money for an air force warplane.[5]

nationalism created by these women in factories soon spread to other sections of Europe. In Scotland in 1918 some shell working Scottish women raised and funded the money for an air force warplane.[5]

Not all of these effects for women were positive however, Eric Leed argues that the new opportunities for women in World War I created, “an enormously expanded range of escape routes from the constraints of the private family” because the war caused “the collapse of those established, traditional distinctions” that usually restrained women’s actions.[6] This is an unfavorable trend formed by working in the factories. Soon women lost the genteel ideals which had been instilled in them since birth. This can be seen also in other forms of life such as the carnivals of the early twentieth century.

t. Organizations such was the Queen Mary’s Army Auxiliary Corps (QMWAA), served as an outlet for these ambitious women. Also the new dependencies on industrial production allowed for women to find work in places such as munitions factories. For example, in the beginning of WWI in Britain, close to one million lower class women soon found themselves working the munitions plants of Britain. These women soon became known as “munitionettes”. One downside to becoming a woman activist is that munitions experts and employees’ work contributes to the fighting, they are not able to profess their pacifism. The soon increasing

t. Organizations such was the Queen Mary’s Army Auxiliary Corps (QMWAA), served as an outlet for these ambitious women. Also the new dependencies on industrial production allowed for women to find work in places such as munitions factories. For example, in the beginning of WWI in Britain, close to one million lower class women soon found themselves working the munitions plants of Britain. These women soon became known as “munitionettes”. One downside to becoming a woman activist is that munitions experts and employees’ work contributes to the fighting, they are not able to profess their pacifism. The soon increasing  nationalism created by these women in factories soon spread to other sections of Europe. In Scotland in 1918 some shell working Scottish women raised and funded the money for an air force warplane.[5]

nationalism created by these women in factories soon spread to other sections of Europe. In Scotland in 1918 some shell working Scottish women raised and funded the money for an air force warplane.[5]Not all of these effects for women were positive however, Eric Leed argues that the new opportunities for women in World War I created, “an enormously expanded range of escape routes from the constraints of the private family” because the war caused “the collapse of those established, traditional distinctions” that usually restrained women’s actions.[6] This is an unfavorable trend formed by working in the factories. Soon women lost the genteel ideals which had been instilled in them since birth. This can be seen also in other forms of life such as the carnivals of the early twentieth century.

From the European perspective, women were not always seen as just aids to help the men on the front line. Many countries, such as the United States of America, used women simply as aids. “They helped nurse the wounded, provide food and other supplies to the military, serve as telephone operators (the “Hello Girls”), entertain troops, and work as journalists.”[7] Women basically played the same role as they did on the home front; to keep their men happy, in good health if wounded, to cook meals, and repair clothing that possibly lost a button. If the women were not involved firsthand with the military performing these duties, they were used to literally shame men into going into battle. “In Britain and America during that war, women organized a large-scale campaign to hand out white feathers to able-bodied men found on the streets, to shame the men for failing to serve in combat.”[8]

Most of the countries involved in World War I assigned women with the same roles, with the exception of some nations like Russia. The Russians did attempt to shame the men into fighting, but through a different method. Though it was not fully accepted, women in Russia were not restricted from enlisting in the military. Originally, women who wished to join the military dressed up as men and cut their hair in an attempt to conceal their true identity. Others though, such as Maria Botchkareva, went directly to the czar and ask for approval to openly enlist. After proving women could fight in battle, women like Botchkareva requested the approval of an all female battalion; thus the Battalion of Death was formed. The Russian government used the women’s battalion in two ways: as normal soldiers to fight on the front, and as objects to shame men into fighting. The idea was to send with Battalion of Death to the front and have them basically out-perform their male counterparts. The Russians hoped that the men would then feel as if they were the weaker of the sexes, and thus they would attempt to out-perform the women and more willingly go into the trenches. The Russians soon found though, that these tactics would not work. Though the women were sent over the trenches to advance in an attempt to encourage their comrades to fight, it ultimately proved fruitless. The somewhat fourteen million Russian soldiers all across the front remained static. The operation proved only to work mildly within the few miles where the Battalion of Death had led the charge. In fact, only about four hundred men in the trenches alongside the women were willing to fight with them.

[1] http://digital.lib.umn.edu/IMAGES/reference/mswp/msp02056.jpg

[2] St Crispen’s Day Speech, Shakespeare’s Henry V, available at: http//www.chronique.com/Library/Knights/crispen.htm

[3] http://www.firstworldwar.com/photos/graphics/cnp_turret_guns_01.jpg

[4] http://digital.lib.umn.edu/IMAGES/reference/mswp/msp02038.jpg

[5] http://www.warandgender.com/wgwomwwi.htm

[6] http://www.warandgender.com/wgwomwwi.htm

[7] http://www.warandgender.com/wgwomwwi.htm

[8] http://www.warandgender.com/wgwomwwi.htm

5 comments:

I think you guys did a very good job. You analyzed your pictures in a way that related to your topic. Also, in doing so, it flowed nicely. The one problem was some of the pictures were hard to see. The one with the tank has a white box over half the picture, and another one is too small to read. However, I thought you did a good job with your analysis of the pictures and relating it to your topic. Finally, I liked how you related your topic to All Quiet on the Western Front.

I thought you guys did well in staying on topic and using pictures and sources to prove your research. You had great insight and interesting ideas. You could have used a stronger hook sentence to get the reader's attention at the beginning of the essay and your transitions could have been smoother, but all in all great job.

It got the point accross but it was kinda awkward. some sentences seemed to come out of nowhere and there were some strange wording.

No theses

Lots of things that Mr.Sabato says

Pete, Ryan, and Pat,

I think you got the main concepts of the topic at hand and did your best to articulate how the Great War affected gender identity. One aspect of your analysis, however, needed some more depth and clarity. The "shaming" of men by women is a very powerful example of the way that gender shaped the war effort, so you were right to point it out. In the context of your argument though, which saw women has auxillary and supplementary to men in the war effort, the "shaming" doesn't fit. Thus, how did the handing out of white feathers to able bodied men in order to shame them into service complicate, reinforce, or counter your view of the gender dynamic at work during WWI?

Overall Grade: 4

Post a Comment